Every region is seeing

the effects of climate change

Interview with

Valérie Masson-Delmotte

The 2021 IPCC Working Group 1 report described the current state of knowledge, and what practical tools leaders can use locally to assess climate risks and make changes to mitigate them. Deltares had the opportunity to speak with Valérie Masson-Delmotte, a senior climate scientist and the co-chair of the IPCC Working Group 1 (which works on the physical scientific basis of climate change) about the IPCC Report and COP26. Her knowledge and insight make important and accessible reading for everyone from government officials to businesses and citizens.

What did you think of COP26?

“I saw some new things at this year’s gathering. More time was set aside for the presentation of the IPCC report released in August 2021. We were given three hours to present the main findings and address questions. I was impressed by the quality of the questions asked about the report, and by the number of delegates and negotiators COP26 who had read and understood the report and its implications. They understand that every region is impacted, that climate change is intensifying, that every region is feeling the effects, and that human activity has caused it.

“Many countries concerned about sea level rise picked up on the projections of when a certain level will be reached. That is of vital importance to them now: not just the number of degrees of warming in the coming decades and centuries, but also 50 cm, 1 m, or more of sea level rise expected as a result of past and future greenhouse gas emissions.”

“What is critical for me as a climate scientist is that the best available knowledge should be used for education, teaching at all ages, so that people can build on today’s knowledge to inform their decisions and choices. Developing climate literacy is part of the solution in my view.”

Valérie Masson-Delmotte

What are the main conclusions of the IPCC report?

“What is on the negotiating table is not sufficient to keep warming at low levels. There are still important questions about effective implementation and about mechanisms to allow for faster reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. They were not covered at this COP but the delegates did agree to allow for annual revisions of pledges. That is vital.”

How can we deal with uncertainties, events that might not happen but that would have severe impacts and cannot be ruled out?

“In our report, our working group (WG 1) concentrated on robust findings, facts in which we have high confidence. We also have to analyse events with a low or unquantifiable probability but severe consequences and/or a devastating scale of impact. ‘If this situation arises, this is what is likely to happen but we can’t specify the timing or extent.’ The possibility of the collapse of ice sheets is an example of dealing with uncertainties. We were asked to look into this by leaders working on critical infrastructure and coastal cities. They need to know the maximum plausible amount of risk so they can plan with a wide margin of safety. They can then design infrastructure accordingly. Work has advanced on the impact of sea level rise and there are now best estimates for sea level rise for different warming scenarios. In the worst-case scenarios of GHG emissions, the instability of ice sheets could double by the end of this century.”

Compound rare events

If a region experiences, for example, both extreme heat and drought at the same time, the results can be severe. If several breadbaskets (typically grain-producing agricultural areas that provide much of the food needed by other areas) around the world are affected by more than one event at once, that could sow chaos in global food markets. And the most vulnerable people would be most impacted. For every degree in temperature rise, rare events become more likely.

"We were asked to look

at how to deal with uncertainties by leaders working on critical infrastructure and coastal cities. They need to know the maximum plausible amount of risk so they can plan with a wide margin

of safety”

How to avoid an alarming tone and despondency?

“I am always puzzled when observers stress ‘an alarming report.’ The report just reflects the current situation and state of knowledge. When we assess knowledge about these risks, we can be seen as alarmist. But the situation itself is alarming – we are continuing to emit more and more greenhouse gases. We try to give a factual explanation of the knowledge we do have and how it can be used.”

Interactive tools for risk management and training

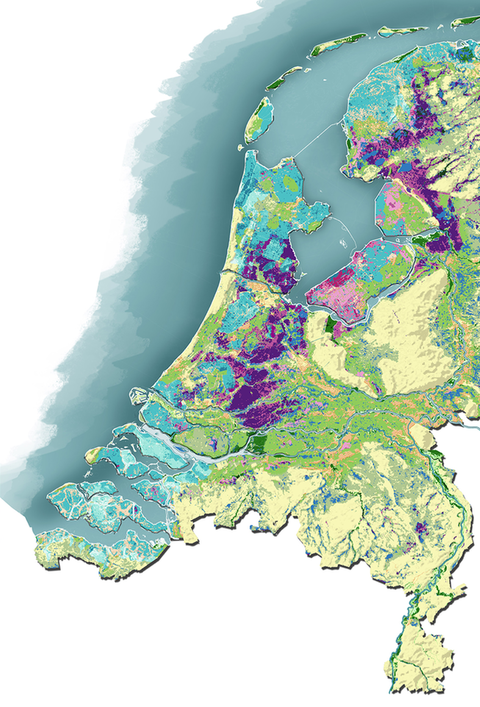

Interactive tools are now available for public use. NASA has a tool to map sea level rise. IHE Delft has created one for coastal conditions. IPCC itself made the Interactive Atlas at the regional level, which includes several factors (degree of warming, timeline, etc.) based on climate model results, for the purposes of education and training. That makes it possible for people to access and extract the climate information to make their own visuals.

For example, if you are looking at fire and weather, you can look at which regions will be impacted when warming reaches two degrees, making preparations and risk management possible.

Deltares can use these tools for training and teaching, and to develop more details, more granular information.

How can leaders use climate information for risk assessment and adaptation?

“The report provides knowledge, one third of it at the regional level, to be used in an open-minded approach to incorporating science in decision-making and to prevent further damage on top of what we already have. Risk assessment must be added to records of past events, local information, context-specific circumstances, and the needs of users to make decisions.

“This research can also be important in terms of looking forward to how these events will evolve, as well as in terms of stress testing for risk. Regions can use it to inform adaptation strategies, forest management, coastline management and the design of buildings.

For building on coastlines, changes can be made to building codes for resilience; designing and building for future conditions is less challenging than upgrading later. In terms of governance, to what extent are officials obliged to use this information to inform decision-making about permits, building codes, run-off water, sewage or vital infrastructure? How can they include ‘resilience thinking’ in their work?”

How many institutes were involved in the IPCC report and how important are they?

“Research institutes will be increasingly critical. WG 1 builds on the physical science base but, more and more, we are also building on how to frame climate information so that it is actionable and useful to inform decision-making. This is a major advance. Applied science and expertise such as Deltares has will be vital at the interface between the physical science and the work of engineers and practitioners in the field so that solutions can be useful and effective. For the first time, in this report, we have a dedicated chapter on water and there will be more (WG-2).”

“An open-minded approach to incorporating science in decision-making and to prevent further damage on top of what we already have”

What drives impacts and risks?

“The report identifies thirty-three Climatic-impact drivers, physical characteristics that drive impact and risks. This is IPCC’s way of providing actionable information that is directly relevant to impact and risk. Things that unfold slowly, like gradual trends in rainfall and rising water, can exceed current infrastructure tolerances relating to, for example, storm sewage limitations. Events can gradually outpace a region’s capacity to cope.”

What now?

“Two more IPCC reports are due soon: one on impact and risks in February 2022 and one on mitigation in March 2022. A synthesis will be released in September 2022.”

Contact person

Bart van den Hurk

Climate expert